I am showing some new volunteers around our local permaculture Food Forest introducing them to as many trees, shrubs and groundcovers as I can remember. A major aim of the Food Forest is biodiversity. This means nurturing as many plants as possible, both the ones we have planted and those who have turned up uninvited, some welcome, some not. They all have multiple names, and my memory and knowledge of them is very much a work in progress. Having performed the role of tour guide for a few years now, I still have to answer the question “what is that ?” with “I don’t know” a few times each tour. But once it would have been much more. Each working bee in the Food Forest, I learn another name and hopefully with it a story or two about who this plant is, how they interact with soils, insects, birds, other plants and humans.

Like many people, I struggle to remember names – people’s and plants. Each working bee, we volunteers start by going around the circle reminding each other of our names. And just as with plants, slowly the names stick. What surprises me is how I can recognise a person, remember a few things about them, like where they live or the work they do, but still their name escapes me. Names it seems often come last in our mental ordering of others.

Years ago, I had the privilege of doing several workshops with Yuin elder, the late Uncle Max Dulumunmun Harrison, a First Nations teacher of great wisdom and heart. Each day Uncle Max would take us in to the bush, telling us about the plants along the way, referring to them as “this fella” and “that fella”. He commented on how Europeans were often hung up on getting the correct names for plants yet rarely bothered to stop and converse with them. Knowing the names, Uncle Max said, was not what mattered, what mattered was to recognise plants as our fellow beings, our kin. Much better, he taught us, to address plants directly and listen to their messages than to refer to them in passing by some fancy Latin name, often celebrating the white man who had supposedly ‘discovered’ them. I took Uncle Max’s teachings to heart, as did everyone who had the privilege of meeting this warm and generous man. So now, I don’t fret over unknown plant names, but I do take time to appreciate and thank them for their gifts.

Names however do come in handy when we talk about plants with one another, as we need to do in order to learn about and care for them. And some plant names can carry a wealth of history and information. Forty years ago, I trained to be a herbalist. My years of studies firmly lodged the Latin names of many herbs in my brain. The names I cherish most however are the so- called common names, rich in descriptions, associations and history.

One of my favourite herbs which I have no problem recognising is lemon balm or melissa officinalis. She regularly pops up of her own accord in both our Food Forest and Community Garden. All her names are rich with connections. Melissa the Latin name for honeybee tells us that bees love the flowers of this plant and that beekeepers cultivate her in their gardens. Lemon of course refers to the beautiful scent and flavour this plant carries courtesy of its many volatile oils, while balm tells us that this herb is a great cure all for many ailments from anxiety to cold sores. She’s a plant whose character, appearance and name I learnt early on in my herbalist studies, drawn in part I am sure by her attractive names as well as the uplifting flavoursome tea. I am in good company here. Lemon balm was honoured by the mystic Saint Hildegard de Bingen as containing “within it the virtues of a dozen other plants” and dubbed the “elixir of life” by Paracelsus, the Swiss physician and alchemist. In her recent post on lemon balm, Amy Walsh, M.D. writes “This gentle plant clears our heads and hearts”. Perfect drinking for these troubled times.

Keeping lemon balm company in our Food Forest are other types of lemon plants including lemon verbena, lemongrass, lemon myrtle and lemon aspen (or rainforest citrus). While none are related as a species, in flavour and scent they are sisters. The lemon aspen tree, also known as snowberry tree for its tart white lemon flavoured berries, is much visited , especially by children, once we introduce and give them permission to pick and eat her berries. After this they have no problems remembering where the tree is, the taste of the berry, and perhaps even one of her names.

Children love visiting our Food Forest. They are full of questions and observations, often spotting what we miss, especially beetles, moths and lizards. The iNaturalist app comes out and we learn their names together. Experiencing their enthusiasm first hand, makes me all the sadder that so many plant names have been jettisoned from the Oxford Junior dictionary over the last twenty years. Almond, apricot, lavender and ivy have all disappeared from the pages of this highly esteemed children’s dictionary, to make way for the words of digital life, like blog, broadband and chatroom. What this abandonment of plant names sanctions is a devaluing of the basic facts of life, like plants’ oxygen and food production on which our livers depend.

At a primal level, our human instincts are attuned to our living world. Babies and toddlers will happily absorb themselves in dancing leaves on a tree, ants parading in and out of crevices, the movement of clouds across the sky. But in today’s world our young ones have limited time outside. Instead modernity culture hijacks their lively curiosity with the seductive blandishments of digital screens and consumer culture.

When the editors of the Oxford Junior Dictionary justify their decision to replace words of plant life with digital life, they say this reflects the contemporary child’s reality: It’s not up to them to be moral arbiters on today’s culture. But this value-less stance is, I believe, negligent of the life-threatening consequences of plant illiteracy or ‘blindness’. A culture that doesn’t know or value its plants kills forests, poisons soils and pollutes waterways without understanding its undermining all of life.

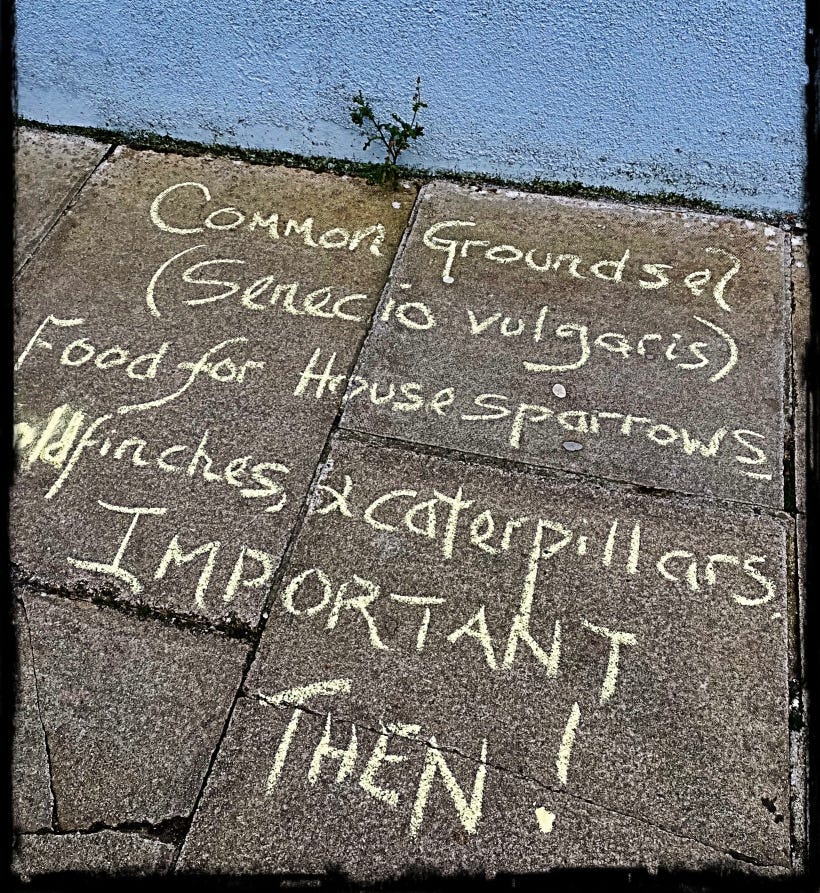

But when human mortality threatens, consciousness of what sustains life tends to sharpen. Little surprise then that during COVID lockdowns, millions of people turned to plants and gardening in numbers never seen before. While many people focused on planting veggie gardens and street verges, British teacher Elizabeth Rishmond went many steps further when one day she spontaneously picked up a piece of chalk, as she headed out the door for her daily walk. As she walked, she started to chalk the names of the wild flowers she knew, or thought she knew growing alongside or out of the cracks of pavements. She writes:

I did it originally to help me remember the names of the little wildflowers I thought I know, then quickly realised I didn’t: Sowthistle, Hawkbit, Dandelion…? Heck, they all looked the same to me! Then I started looking, really looking, and slowly I saw their differences.

With the aid of her iNaturalist app, Elizabeth’s plant knowledge grew as did the company of others, inspired by her to chalk plant names on the pavements of their own neighbourhoods. Together they took on the tag of #Rebel Botanists. Within 6 months, they were featured on BBC Radio and TV. Now this movement has spread across the world and I am ready to join in, chalk in hand.

Writing on pavements is not for everyone, but we can all play a role in fostering plant appreciation. Most important of all is to introduce plants to children. You can plant seeds together in a pot or in the ground, then marvel at the miracle of seedling becoming leaf, flower and then seed again. More than likely these will be the plants children will remember and care about as adults. Or you can go for walk together identifying the wild and wonderful plants that attract your attention. Observe what plants the insects love and what plants smell good. Research what’s edible and take them home for dinner after a thorough wash!

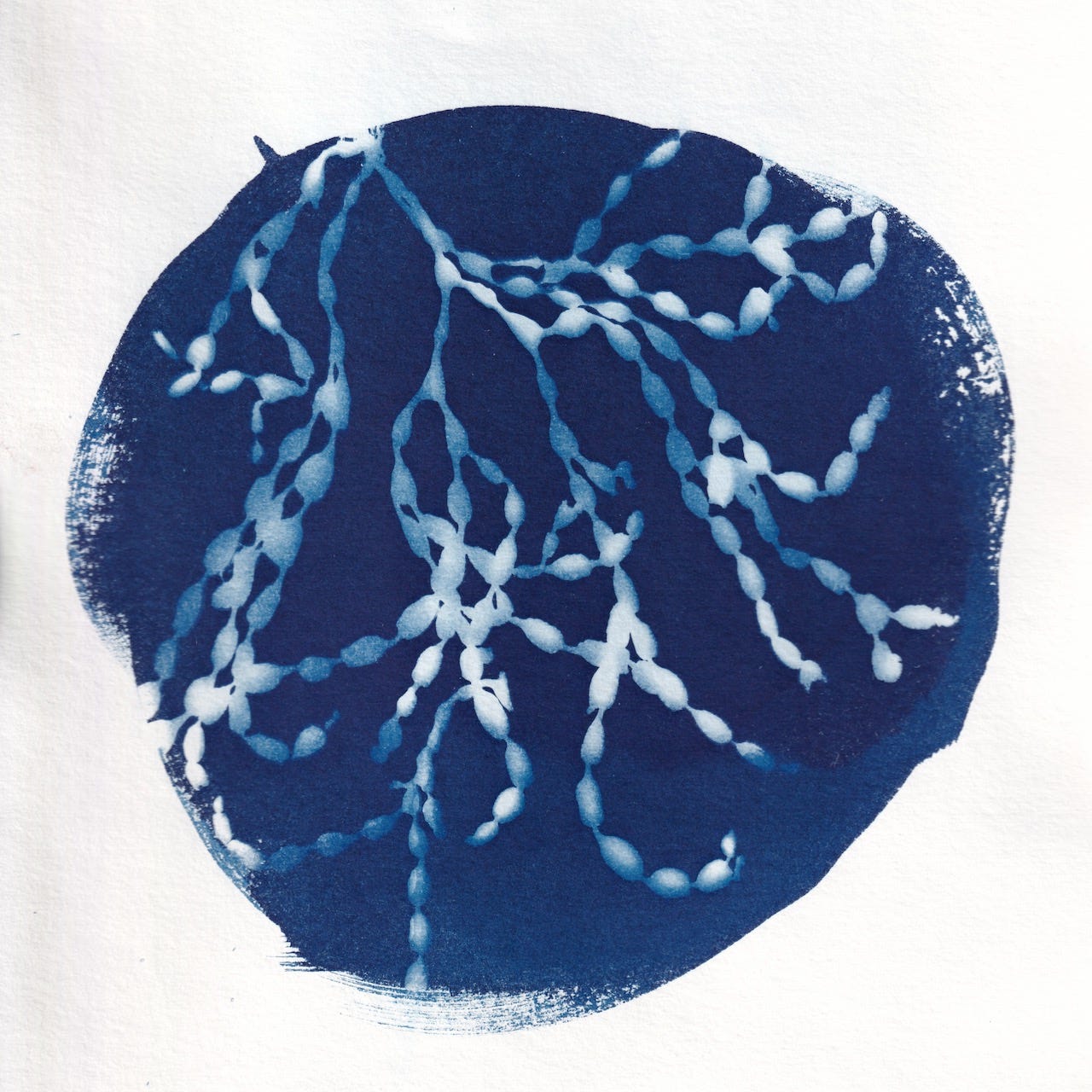

Another way to deepen plant knowledge, at any age, is to take sketch materials or a journal to record your findings. So much of what we know is because over centuries people have drawn and written about plants. I am particularly appreciating this right now because I am reading Olivia Laing’s beautiful book The Garden Against Time: In Search of a Common Paradise. Writing about the 19th Century working class gardener and poet John Clare, Laing reports that over four hundred wild and cottage flowers have been identified from his poems and letters. What an encouragement and lesson for all writers to notice and record the plants now, to make visible what we want to preserve for the future.

While it breaks my heart that ‘plant blindness’ has become an official term in our age, it illuminates what each one of us must do to counter this. When we greet and recognise the plants we live amongst, we germinate the seeds of plant consciousness which can then sprout up in our conversations and writings. Then we can become not only a botanist rebel but a cultural rebel and transformer by honouring our plant kin. There is so much we need to dismantle about modernity culture. Greeting and giving gratitude to plants must surely be one of the most pleasurable revolutionary acts we can do each day.

Substack is full of writers and artists who know and celebrate the plants where they live. Here are a few whose work inspire me:

yes, yes, yes. here's to edible herbs and flowers, to traditional bush medicine, to growing things and loving plants and enjoying wild nature however we can, more important now than ever. thanks, sally, for another wonderful reminder of what is true and good xx

Beautifully and thoughtfully written as always.For all us crones I am sure the plants are watching us and getting our attention to keep us on the right plant track.